Title: Hysteria: Its Cause and Consequence

Lecturer: Manly P. Hall

Event Details:

Recorded on August 8th, 1981, in front of a live audience.

Publication Date: August 25, 2024

Description:

In this insightful lecture, Manly P. Hall examines the psychological condition of hysteria, exploring its origins, manifestations, and broader societal implications. This lecture provides a profound analysis of the causes and consequences of hysteria, demonstrating Hall's deep understanding of psychological and esoteric traditions.

Technical Note:

There are some issues with the Closed Caption (CC) subtitles in the original recording. Efforts are underway to resolve these to enhance accessibility.

Keywords:

stressrelief healingjourney manlypalmerhall

Reference Code: MPH 810830

Rights and Permissions:

© Manly Hall Society. All rights reserved.

Transcript:

A full transcript of the lecture is provided below to assist in following along with Manly P. Hall's exploration of hysteria.

Watch the Lecture Online:

To view the full lecture, visit: [Hysteria: Its Cause and Consequence](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BE8EjQSDthU&t=2492s).

---

This front matter is designed to provide context and essential information for readers, maintaining the focus on the content of the lecture itself for independent sharing.

Under the general heading of hysteria two distinct conditions are obvious. There is a difference between hysteria and an hysterical situation. People are hysterical very often as a result of stress, nervousness, tension, or some sudden emergency arising in their lives. Very often the ground for it is an essentially hypersensitive nervous temperament. Everyone who has a nervous temperament should work on this a little just to be on the safe side.

How do we know whether we are nervous or not? A simple way of determining this is to study the irritation level. What does it take to bother you? How far can you stand certain pressures or stress without reacting in some kind of a semi-irrational way? Are you able to hold your temper well or does it come to a point where an explosion is almost inevitable?

One of the most common problems is to find out whether other people can disagree with you on almost any subject without causing irritation to you. A calm, placid temperament is much less inclined to develop various types of psychic stress. If you have an agitated temperament or a temperament that agitates quickly and easily, you should consider the effects of this upon the immediate environment. In this case, the immediate environment is your own health.

Wherever stress arises in the personality, rates of vibration are set up that disturb normal functions. An individual who is extremely nervous develops a series of ailments which result from lack of nerve control. The more nervous we are, the more likely we are to have at least minor physical complications that are distressing and uncomfortable. We know, for example, that tension affects elimination, digestion, and sleep patterns.

Wherever the person is essentially tense, one of the symptoms is an occasional hysterical outburst. Some feel that this is a very necessary and useful means of letting off steam, but thoughtfulness indicates that it is better to keep the steam low all the time than take a chance that it may burst the boiler on certain occasions. In order to be really in control, unusual circumstances must be met with comparative relaxation.

There was an instance of a secretary seemingly well integrated, very matter-of-fact, impersonal, self-contained, and apparently the embodiment of detached efficiency. One day, however, this secretary made a kind of curious mistake. She opened the two or three upper drawers of a large filing cabinet too far. The filing cabinet started to tip over, losing its balance point. The secretary managed to get it back on its proper basis but practically had a nervous breakdown as a result of the incident. She had to go home and remain there two or three days to get over it. Probably it was not so much the tipping of the filing cabinet as it was the sudden realization that the purely business attitude, the matter-of-factness which had been carefully cultivated, would not hold in a small emergency. Behind this was again the pressure of a natural tendency to emotional distress.

Certain persons apparently have to have periods of emotional or hysterical intensity. They seem to require the shock of letting off from themselves a static kind of electricity which threatens to become a serious issue. Most of this type of hysterical reaction, however, is not a genuine ailment. It is simply the result of habit and personal intensity. It may be the result of frustration of a desire at a moment. All kinds of minor tensions can cause moments of hysteria or hysterical reactions. These sometimes develop in children. Where a child discovers that a tantrum produces the desired result, the tantrum is very apt to become habitual.

If a person has tantrums in their teens or even earlier, they generally make a very important discovery: other people do not like to be made uncomfortable by the disposition of an emotionally stressful person and will do what they can to prevent the stress from developing. As a result, the stressful person is allowed to do as he pleases. This is a very vital discovery. It places the person in a position to control environment by the development of an unpleasant disposition.

When someone acts unpleasantly and we decide to retire from the situation, the result is that the unpleasant person has lost an important possibility for personal growth. He would have been far better off if those around him had stood up to him and opposed an hysterical attitude. That becomes unpleasant, tedious, and sometimes even expensive, so rather than face this emergency, the individual is given into until their disposition is spoiled. They will carry this through life and wherever an emergency arises they will seek to get their own way by an exhibition of unpleasant disposition.

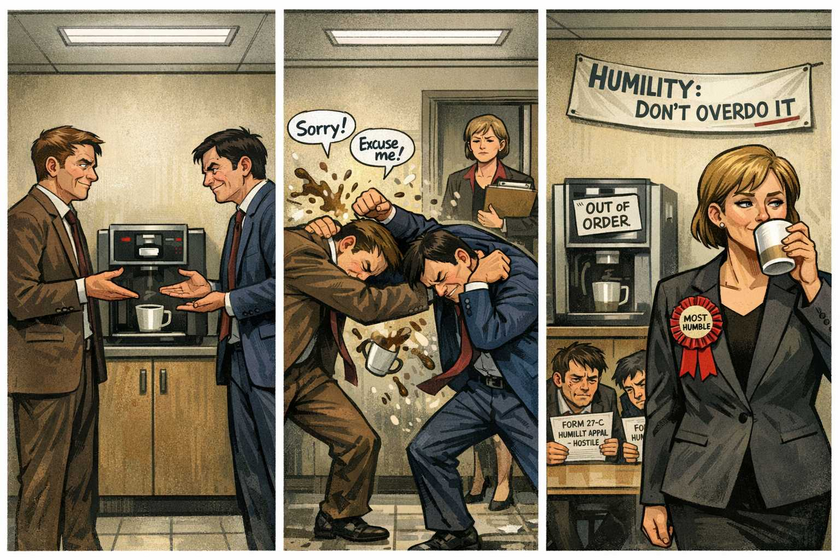

We all, to a degree, have a tendency to cultivate this situation. We have a feeling, for example, that if we talk louder than the other person we are proving something, that we win a debate by some emotional outburst. Actually, we win nothing, but there are a great many people who mistake emotion for rationality and believe that they win by an exhibition of temper rather than by solid judgment or knowledge.

If you find this tendency arising in yourself, if you find the inclination to bluff, to try to force your way through by intensifying emotion, you are probably subject to a modified form of hysterical reaction. If the individual wishes to make the most out of life, it is very necessary to be able to accept that which is not always agreeable. We should be able to face disagreement with calmness, kindness, and attentiveness. We are here to learn and not to overwhelm someone else by the intensities of our reactions.

We are not well off if we permit any form of stress to compensate for lack of judgment. To judge the proper values of things we should be relaxed, self-contained and poised, and we should be very attentive to information that may not particularly please us but which may be very important for our wellbeing.

Most persons have a tendency to emotional outbursts as the result of some form of emotional frustration or disturbance. The individual who has no outlets is apt to develop hysterical tendencies. If we have good physical activity, if we are engaged in sports or we have interesting hobbies and avocational outlets, and are able to keep the mind more or less concerned with constructive activities, there is less likelihood that we will become emotionally distressed.

One of the avenues which points this up clearly is the field of sports. The loser has to be a good sport, and if he loses his temper and becomes unpleasant he is a double loser. He not only has lost the sport, but control of himself. We take it for granted in the sports field that the winner and the loser should still be friends, should recognize the circumstances and not permit disappointment, chagrin, or mortification to interfere with a pleasant acceptance of loss. We have to learn this.

When we go out into the world where things are not as pleasant as they are on a tennis court or in a swimming pool, we also have to learn to be good sports. A good sport will not be in much danger of an hysterical reaction. A wounded ego sometimes causes it, sometimes a sense of defeatism or chagrin, and sometimes resentment against a victorious rival. It can also be a resentment against the failure to get what we want when we want it, a resentment that we are unable to keep up with other people. All kinds of frustration can result in the gradual building up of this tendency to a reaction of hysterical proportions.

Behind the physical body of the individual is what is called an energy field, a more or less magnetic zone. It is an energy distributing area that corresponds with the maintenance of our vital resources. It is this structure within our invisible natures which results in a manifestation of most of the physical body functions. It is responsible for the circulation of the blood and it also maintains the magnetic content of the blood. It contains a nutritional factor and if allowed to function in its normal way this magnetic field is the basis of reasonable health. It is this field which supports and nourishes the body just as food nourishes the physical body.

This magnetic field nourishes functions. It nourishes the invisible causes and sources of our visible activities. It is the basis of our feeling well or feeling ill. Anything that interferes with the distribution of energy through the body is almost certainly going to affect health and disposition at the same time. The magnetic field is always entirely responsible for what we call disposition. It has to do with the attitudes that result from adequate or inadequate distribution of energy resources. The individual who is tired all the time does not have as good a disposition as one who feels better. The person who is constantly depleted in energy is likely to develop negative attitudes, become pessimistic, and lose control of the nervous functions of the body.

If we find a tendency to unusual fatigue, if we find that the body is not supporting us reasonably well, there are several possible solutions. One of course is nutrition by means of which we provide the body with the basic elements, chemicals, and materials it needs for the maintenance of its structure. The magnetic field more or less functions through the level of the bodily nutrition. It is not the source of it, but it does use it as a bridge or means of getting into the physical consciousness or disposition of the person. Therefore, building up physical resources through good nutrition provides in due time a better avenue for the manifestation of the magnetic field.

Maintaining the magnetic balance is a very intricate process. It is this magnetic field which constantly recharges us and gives us the ability to work and accomplish what is necessary. As in the case of an automobile, while we put gasoline in the tank, we still need the electrical system. The gasoline in the tank is the nutrition; the electrical system is the magnetic field. Without either, the structure and function of the car is practically impossible.

Having this combination in mind, we then have to consider how the magnetic field itself is affected in its function of protecting our health. As we know from the old records and from a great deal of the ancient and more modern research, the magnetic field of the human being is a kind of envelope. It is a kind of egg-like structure, invisible, but surrounding the body with a field or aura of energy. This field or aura has a circumference. That which is within this circumference forms a kind of pool of resource. It gives us the basis of our magnetic nutritional support.

The magnetic field is vulnerable in several ways. Magnetic energy is very largely under the control of various pressure making mechanisms within us. If, for example, the physical body is allowed to run down, then the flow of magnetic energy into the body is impaired. Where an impairment of this kind occurs, there is sometimes a byproduct that is unpleasant. If the energy cannot flow properly through the body, it may break out in various areas of the body with conditions that are malignant because it cannot function properly through the structure of the body.

When the magnetic field is blocked, the immediate reaction is loss of vitality. There is a kind of loss that cannot be compensated for by nutrition alone. The individual may try to eat more rapid energy foods, particularly carbohydrates, in an effort to retain this sense of well-being. If he is very, very foolish, he will attempt to do it with alcohol. but this again only results in further depletion and further destruction of the magnetic resources.

Actually, the only way in which the magnetism flowing into the body can be maintained properly is when the channels for its distribution are kept in a healthy condition. These channels react very definitely to attitudes. The physical body basically does not react well if it is not properly maintained. If the laws governing the body are violated, the energy field is not able to come through properly and take care of the person.

Also, the emotional nature has an influence on the energy field. The feelings of the individual are also nourished by energy. Our thoughts, emotions, and physical functions are energy sustained. Wherever this energy maintenance is disturbed, there will be a reaction that gradually extends to all parts of the corporeal structure. The different fields of energy have laws which govern them. Oriental philosophy has long understood this and tried to make it a part of a normal regimen of conduct.

The maintenance of man's nutritional energy, derived directly or indirectly from the sun, derived also less directly but perhaps more empirically from the whole cosmos—the cosmic energy which finally seeps its way into the mechanism of the individual human being, has rules that have to be kept. If these rules are not kept, health will not be maintained. These rules include mostly the proper regulation of the processes of assimilation and excretion, the processes that keep the body healthy.

The body must have the energy necessary to transmute alchemically nutrition into bodily strength. It must also have the power and ability to maintain the functions of discarding that which is no longer useful. If there is a blockage in the flow of energy from the sun through the magnetic field by way of the spleen into the body and from the body to the functions of the body—if these processes are disturbed, if this distribution system is damaged, it adds up to problems and difficulties.

We have learned from the study of nature and from the realizations of the wise that the only way in which this flow can be normal is if the person through which it is flowing is normal. Unless the individual is living in harmony with natural process, we cannot expect these processes to function properly. There are problems we cannot completely control, such as the pollutions which affect the planet at this time, the adulteration of the food products we eat, and the bad habits which are apparently necessary to maintain our economic survival. And we cannot control the endless irritations arising in our relationships, personal and collective.

While not completely soluble, these conditions can be improved. And this improvement really represents a careful estimation of what we must do to retain the rhythm of relationships with natural energy resources. When we break this rhythm or disregard it, we are in trouble and always will be.

The answer for the most part is the hardest for the average person to achieve, namely, simple quietude, a sense of non-resistance to facts. At this time in our political history most people are batting their heads against bulwarks they cannot overcome and also are unable to handle facts. They resent and downgrade them. While they know they are not right, they also have another fact—that in most cases there is nothing the individual can do about it.

The best solution to all these difficulties is to retain as far as possible a normal relationship with life. We have to live with our own relationships. We have to live with the kind of world our mind, emotions, energies and intensities create for us, and we must keep the pressure low. If we do not keep the pressure low there will be these occasional or sometimes regular outbursts of dispositional violence. They have always been there to some degree, but they are becoming more intensive. This is probably best indicated by the violence that is breaking out all over the world, violence represented by murder, by all kinds of crime, by international discord, and by the continuous development of irritations. Today it is almost impossible to find a country that is not dramatically irritated about something, or to find an individual who is not irritated about something.

Now irritation is an irritant; it is not a force for good. Any stimulation that seems to come from irritation is false and the individual is thereby undermining himself and deflecting from its proper purposes the energy of the sun upon which he must live. He is abusing this energy to maintain his grudges rather than using it to develop the resources of his own nature. This philosophy might not be so sound in its applications if our physical existence in one life were to extend for two or three thousand years, but with only a comparatively moderate span of life, the possibility of a solution of the major problems which concern us is very slight.

Instead of trying to stall these problems by a head-on collision, the best thing we can do is relax and try to plan and revise as rational and intelligent manner of handling these problems as is possible to us. Where we cannot achieve some form of control over our own reactions, we come to these hysterical outbreaks to the point where we cannot take the stress any longer.

Something has to give. In politics this ends in riots, civil wars, rebellion. On another level it ends in the disruption of our economic, industrial, and even our agricultural systems. The reward of violence is hunger, pain, and disruption. Yet violence is so close to the surface in most of us that it takes a certain amount of care and thought to make sure that it does not erupt unpleasantly.

Now let us consider for a moment the other aspect of this problem, and this is hysteria per se. Hysteria as a clinical ailment, as a diagnosable disease, is rather different from the hysterical outbreaks of the individual who lacks self-control. Very often a serious hysteria represents a psychological problem and it also can definitely represent a long hereditary pattern. A great deal of hysteria in its pure sense is hereditary. It is not carried forward through the bloodstream necessarily, but carried downward through the psychological integration of several generations of forbears.

Hysteria of this type is very often not accompanied by any of the common symptoms that we refer to as hysterical. In a great many cases hysteria has no visible symbolism of violence. Hysteria may be a complete neurotic withdrawal. The person may withdraw completely into himself and remain isolated. In this case the general attitude is that the person is licking his wounds. Actually, though, hysteria can be a withdrawal from society. When it is this it is often the result of a bruise, a trauma, or a painful circumstance.

Clinical hysteria is probably one of the ailments which has contributed to the monastic way of life. It is the reason many persons depart from the material world and its activities by retiring into the cloister, living a lonely isolated life, or going out to live in the wilderness by themselves.

This escape through isolation does not necessarily mean that the person recognizes that he is directly running away from something. He simply finds that his nervous system, sensitivity, and sensibilities are such that almost every material contact hurts him. Instead of being able to cope with things, he is bruised, disillusioned, disappointed. And as the condition extends itself through his life, it finally can reach the point in which the person is disillusioned in everything, even in himself. This type of complete withdrawal is a very difficult ailment to face or to work with, but it is something that has to be considered from a psychological standpoint.

This withdrawal, however, may be and often is associated with some mechanism that justifies it. Very few people withdrawing from life or wanting to live in an isolated way say that they do not want to meet people or they do not want to be around people.

Very few people withdrawing from life or wanting to live in an isolated way say that they do not want to meet people or they do not want to be around people. There is a reason that develops in the psychic integration that makes it increasingly difficult for them. One of these kinds of problems is the development of a whole series of pseudo ailments, many of which are still diagnosed as major diseases, but actually they are hysteria.

One type of hysteria, for example, can be a pseudo heart condition. Many cases of so-called angina pectoris, which is a painful and dangerous ailment of the heart, are not heart ailments but a form of hysteria. The individual has developed a symbolic mechanism to prove why he cannot do the thing that subconsciously he does not want to do.

Another type of ailment is hysterical paralysis. A person may have every symptom of paralysis and yet it may not be a genuine case. The individual is trying in one way or another to accomplish a definite purpose: either withdrawal into self, or the creation of sympathy on the outside by which he comes to be catered to or taken care of as an infant might be—a regression into infant dependence.

An example of one of these cases is the story of a paralyzed woman in a wheel chair who had not walked for years. While seated by the side of a swimming pool in a wheel chair, one of her grandchildren fell into the pool. The child could not swim and began to sink and scream for help. The woman who had not walked in years got to her feet, got into the pool, swam to the child and got the child and herself out of the pool. She did not go back to the wheel chair, although she had been diagnosed as a hopeless paralytic. This type of paralysis is a psychic form of hysteria which gradually develops all of the symptoms of the genuine thing, but which actually does not have any physiological foundation.

This has a bearing on another field that is somewhat controversial, but in fairness to all concerned it should be mentioned, namely, the problem of faith healing. All faith healing does not deal with hysteria; there is no question about that. But there are cases in which faith has produced a release from hysteria. If faith is stronger than fear in a particular case and the cause is hysteria rather than the actual ailment, it is quite possible for faith to cause the individual to have the strength of character to recover from his ailment, the attitude being, of course, that the individual is not recovering by his own effort but the concept which arises in the mind and consciousness that any person united with God equals a majority, and therefore that the presence of the Divine accomplishes a miracle.

Now there are people also who have various recoveries from ordinary ailments. Most doctors are aware of the importance of the placebo. There is a mass of hypochondria floating around in this world. In its more obvious and simple forms we are able to cope with it, but there comes a time in which the hysteria develops to proportions with which it is very difficult to cope. This situation is always possible where there is lack of emotional integration and personal control.

If the individual is building character, particularly if he is using some simple but effective self-discipline and is determined to devote his life to useful purposes, the tendency is for nature to step in and help cure the hysteria. The person who goes out into the wilderness to live by himself because the world has hurt him or because he feels this complete absenteeism from society is a spiritual break—this person very often just gets worse.

Cuddling his own hysteria to the end of life, he never realizes the mistake he is making. If these persons who are unable to withstand the pressures of society would turn their attention to helping other people, serving, and trying to do some good every day in a practical and simple manner, there is a great possibility that their hysteria would be overcome.

In one instance, a man teacher at a university was finally required to retire because he developed a very strange stammer and began to stutter. He took a number of courses in recovery, gained some benefit from them, but in a short time his stammering returned. In early World War II there was a shortage of teachers. This man offered to take on as a volunteer work in which he was experienced, if the class would accept his limitation of speech. He could talk, but not fluently, and his speech was often broken by his stammer.

After some consideration, the student group, a small class involved in a highly specialized subject, agreed that it would be better to have him than not to have the class at all. He taught this class for the better part of two years. After the first month the stammering began to diminish and before the term was over he was speaking perfectly. This man told me that the reason this change took place was a constantly increasing sense within himself that he had to do better because he could not fail these young people. By degrees, with determination to accomplish his purpose, a complete correction of what had been diagnosed as an incurable state of affairs resulted.

Wherever there is a tendency to a morbid hysteria, where hysteria is an escape mechanism, or where an individual is unable to accomplish what is necessary or has no necessity in life, the first step to solution is to try and meet this need by a practical commitment of some kind.

One problem, of course, that is not generally recognized is that parents, when their children are grown, generally find their lives have less significance. They have done their job, the children have gone and are building homes of their own, they are making their way out in the world, and the parents have become more or less free.

Freedom of this kind can become a cause of hysteria. As the old saying goes, the devil finds something for idle hands to do. Parents raising children find it a mixed blessing, but they also come in time to recognize the responsibility and carry on, certain that when the job is over they are going to rest. When the time comes to rest, they find they cannot.

They have had too much activity. Furthermore, the average person who is resting begins to recognize resources within themselves which have been neglected. Young liberated parents in their forties or early fifties may find that it is very vital to go back into their business or profession. If they do not go into something that is constructive and purposeful, they may begin to develop a certain sense of frustration. They are sorry for themselves but do not know it. They are not functioning constructively and as a result this tendency to hysteria develops, which can become very serious if something is not done to correct it.

Another cause for genuine hysteria is pain. There are a great many people who in the course of life pass through long periods of pain. There are those who have, for example, been wounded or injured in war or in the general accidents of industrial society. There are others who have developed ailments that are not entirely curable but can often be controlled; however, there will be pain. Some ailments are much more painful than others and many of the most painful of all are associated with advancing years.

Pain of this type can result in hysteria. It can become a nervous problem so acute that it affects every aspect of the temperament and character. Some persons with this kind of pain would like to be and often think they are brave enough to handle the situation. They do not want to wish it on their friends, nor be hampered and become objects of pity. Yet this pain goes on, and if it is secreted, held within, and lived with over a period of years, it can result in some type of hysteria.

Hysterias are not always found in the form of ailments. Hysterias can occur in the form of addictions or dedications to unusual or peculiar services in life. One of the outlets for hysteria has always been religion because in religion the individual comes under the pressure of a tremendous power of suggestion. Many hysterical persons or genuine cases of hysteria are benefited by religious allegiances. They also very often carry with them activities.

The religious dedication may lead to the ministry or to various social problems; it may cause the individual to take part in world plans for the benefit of the sick, the poor, or the troubled. Religion provides a field of service. By sharing in this field of service the tendency to hysteria is markedly reduced. It is an outlet that keeps the individual from constantly concentrating on his own aches and pains. A person who has any kind of a physical disability that is uncomfortable, humiliating, or a source of self-condemnation or self-pity, should most certainly find an outlet and stay with it until he is able to extrovert his inner tensions.

Generally speaking, a relief from hysteria must be involved in some kind of a direct physical activity. This energy must be channeled and the magnetic substance which is coursing through us be given a proper outlet. Hysteria is seldom corrected merely by a voluntary mental statement, by listening to others, or by becoming converted to something. The true solution lies in the development of an energy activity which reopens and restores the flow of the magnetic forces in the human body.

Therefore, persons who wish to give their lives to a religious purpose will find it wise to find some religious outlet in which they are kept busy, and physically involved. They should definitely be doing something useful, something that gives them a sense of achievement. Otherwise, the therapy will not be what they had hoped it would be.

Improving personal knowledge is another cure for hysteria. The man who graduated from medical school with a doctor of medicine degree in the same class with his own son is an example of this, someone who had reached an age of liberty and freedom, yet was not fulfilled. Where the life is not fulfilled, self-pity is more likely, and a great deal of hysteria is founded in self-pity.

If other factors are not conducive to security or relief, the individual can advance an educational purpose, taking on subjects that he was unable to complete during his earlier years. He can go every day to earn a degree, or he can attend without credit. He can take up languages, art or music, or whatever his own life seems to need, but he should strive for something. He cannot solve it just by listening to someone else play music; he must become involved, even though it is done very amateurishly. There are instances of musicians whose music is never beautiful except to themselves, but it is that which is significant. It is the satisfaction of self-expression which is so very important.

Other types of hysteria sometimes result from a repetition of unhappy incidents. A person who has a series of bereavements which make it seem as though an ill fortune or an adverse fate were dogging their footsteps, or the person who having found happiness and security has it suddenly taken away from him—the sudden loss of that which is important is very often involved in hysteria, especially if this loss is one of companionship.

Those who have gone through this experience can and very often do feel a certain sense of being heartbroken. They are never going to be able to recover from the loss and will always remember the tragedy. In the course of life most people manage to accumulate two or three tragedies so that this pattern, once it is established, can cause the person to escape or deny participation in life. Where this happens there is always a great danger of hysteria.

Another problem that we have not noted sufficiently in the past is that the treating of hysteria can often contribute to it. The individual who is under these various pressures may seek help and be medicated. Medication for hysteria or for hysterical outbreaks is a very uncertain way of handling the situation. It is known, of course, that there are a great many neo-psychotics who are on medication constantly and as a result are able to return to society with reasonable success.

Where medication can accomplish these procedures there is always the possibility that the protection given by the medication temporarily could invite the patient to the correction of the cause in himself, but if the cause is hysteria, the hysteria itself cannot be medicated; only the symptoms. If the person is in the condition he is in because of a very basic dispositional or temperamental deficiency, this has to be considered in its own right.

For example, there are a great many young people who in this day and age develop either superiority or inferiority complexes. The person with an inferiority complex can sometimes be bolstered up, but the superiority complex is an extremely difficult thing to deal with—not only for the person but for all around them. Those individuals who really feel that they are destiny's darlings and have been frustrated all the way along very often develop definite hysteria, actually becoming involved in what are now considered to be pathological symptoms. The person with the inflated ego who cannot accomplish his purpose will have the tendency to develop hysteria.

The reason for this is very simple: the will to be, the desire to be, the conviction that one can be is grouped at one end of a situation; at the other end of the situation is a personality incapable of fulfilling those pressures. The individual is in his inner life a magnificent example of superiority, but in daily living is more likely an example of inferiority. Not apparently able to do anything important and not interested in doing anything that is not important, the limitations of his development or, as it has been called, "the problem of organic quality," in which the body, the brain and nervous system are not up to the ambitions of the ego, cause a pathological condition in which hysteria very often can develop, and does.

Individuals cannot get well so long as they believe that health means the inalienable right to dominate other people, to do whatever they please themselves, to be completely superior when, in reality, they do not have the capacity for it. This type of hysteria needs reorientation that is very difficult to get. These people do not marry well, do not become good parents, often have abilities sufficient to make a good living, if they use them, but much of the time they will be out of employment because of the tension and stress periods that develop within themselves.

To have a fairly good life it is much better to be moderate in ambitions, grateful for the abilities one has, and to try to expand usefulness without overdoing it or developing psychoses of grandeur— something that is not even possible of fulfillment.

There are certain cases in which the individual comes into a hysterical state through shock. Shock may be a terrible physical shock as in a great and severe accident, or a psychic shock as in the case of infidelity in marriage, the tragedy of the loss of a child, collapse of a business, or the realization of being afflicted with a serious and maybe fatal ailment.

All of these things can produce shock which has a tendency to short circuit the magnetic field. The result of the shock is that the entire system goes out of whack. The individual has blown a fuse in his psychological endocrine structure. This can be a very serious and troublesome problem, but once the shock begins to subside, nature steps in.

In order to endure a shock the individual must support it beyond the pattern of the incident itself. He cannot suffer the same pain twice. We may have a new pain, but we cannot suffer the old one but once. We cannot go through a certain experience itself but once. There may be other experiences, but somewhere within ourselves we have to face up to the problem of these experiences that do arise. We can hope that they will not come in our lives, but they may.

Where this type of thing occurs, the individual shocked may retire from humanity into himself. The shock gradually becomes chronic. When the individual blows a fuse and it is replaced in the near future, the circuit goes back into action. But if the circuit is left without being repaired over a long period of time, it may become incurably broken. Where there is a stress of great intensity, the problem of recovery becomes an immediate situation to face. The person must rise above the problems that confront him and withdraw from the issue. Sometimes he will wait too long to try to do so.

Persons under very heavy loss or tragedy have often been advised to go away for a while — a long vacation or a trip to some interesting place would help them. While this advice is more or less traditional, it does help in some cases. But much depends on how soon it is done. If the individual soon retreats from the situation he has a fair chance of success, but if he waits for a year or two to get around to doing it, the probabilities of improvement are very small, unless he is already improving from other causes.

Again, if a sudden condition creates a short circuit in our lives, it is better for it to be faced by an immediate, sudden constructive experience that will help to take up or compensate for the problem.

Hysteria can also result in various complications such as an hysterical stomach. Stomach hysteria is of two kinds. One is the chronic type that arises from the fact that the nervous system has fixed upon the digestion and the stomach as a particularly weak area. A person who is finicky about food and develops all kinds of antagonisms toward food sometimes will develop hysteria if forced to eat foods that cause this attitude.

One of the most common reasons for that is dieting, where a person on a diet is forced to live largely on foods that they object to. This type of food usually will not digest well and the result is irritation in the stomach and the possibility of ulceration.

On the other hand, shock or stress will cause a sinking feeling in the solar plexus which is related to the stomach and digestive system. Hysterical outbreaks injure digestion, and by so doing badly unbalance body chemistry. As a result of a bad dispositional outburst, the entire digestive, assimilative, and excretory systems are adversely affected. The more nervous, the more excitable, the more tense the person is, the more he is likely to have problems of elimination and digestion.

Many people today complain of this type of problem and a great number of them are using various artificial means to improve elimination. The best way to improve it actually is to maintain a proper constructive attitude while eating. If an individual carries a grudge to the dinner table, he will regret it. The Chinese discovered that a long time ago, also that the meal was not improved if the cook had a grudge.

And while we are not sure that the purveyors of TV dinners have grudges, still perhaps the indifference, the complete commercialization, the lack of thoughtfulness, the lack of individual involvement in the preparation of these foods may have an effect upon their digestibility. This is regardless of the quality of the merchandise which, incidentally, is likely not to be too good. But the person who is irritated, uncomfortable and unhappy will have stomach trouble, will not be ableto eat properly, will have erratic eating habits, will have poor elimination, and will be worried to death about everything. It all fits into a pattern.

The individual who enjoys his food is far less likely to be a hysterical person simply because he finds relaxation and the digestive processes go on unimpaired. The moment we impair a function we begin to defeat a disposition. The moment we defeat a disposition we use the magnetic energy of our invisible electrical equipment unwisely. We begin to pervert energy. The perversion of energy can do all kinds of things. One problem we are having now is the problem of what happens in an accident where we are having atomic or neutronic research. We know that the nuclear waste is endangering the planet.

Analogous to this, we have nuclear waste inside of ourselves. Wherever we use natural forces unwisely, we are doing the same thing that humanity is doing when it is using universal energy to create an instrument of destruction. Destructive attitudes have their energy wastes in our bodies. These wastes pile up and develop into toxins and the more toxic we are, the more subject we will be to some type of hysteria. Where there is a good digestion and the individual sleeps well, hysteria is not so much of a problem.

This brings sleep into focus. One of the most interesting problems of sleep is that it can be a defense mechanism and an escape mechanism. The individual may retire into sleep to avoid the world. He may retire into sleep to restore the body, which is its most natural and proper usage. He may also attempt to escape into a world of fantasy. Sleep may be a way of getting away from himself, forgetting his own existence. If he wants to forget his own existence he likes to sleep a long time. If, on the other hand, he is too busily engaged in almost any activity that requires consciousness, he may become short circuited in his sleeping mechanism and not get rest enough.

The person who is suffering from hysteria is often a poor sleeper. He has problems of rest which have not been solved. He may go to sleep but he will waken up tired and unrefreshed. He will find difficulty in getting back to sleep, and then the awful thing happens. The individual begins to think. By the time he has thought his way through every impossible situation that might arise in his conscious life, by the time he has remembered every misery he ever went through and becomes ever fearful of the outcome of his present undertakings, he is really in a sad way.

To meet this emergency we have the famous over-the-counter remedies by the millions. The tremendous sale of these indicates beyond doubt that a very large part of our population does not sleep well, and that does not include the group that is under medical prescription sleeping aids, but only those who are trying to get away from the pressure of the day.

Sleep is a good answer to many problems. Much concerning sleep and rest is involved in what happens an hour or two before sleeping. The last part of the day, the hour or half hour before you hope to sleep, should be in some way an invitation to rest. It can be good music, a good book read for a time, good thoughts, or plans for better things to do tomorrow. It can be reminiscence over the joys of life or a very devotional attitude of gratitude to the world, to God, and to our friends and family for the benefits that we enjoy. All attitudes that precede sleep should be constructive; everything negative should be held in abeyance.

A great many reports are coming in of the detrimental effect of television programs on sleep. The individual who just finishes a program with four or five murders in it and then tries to go to sleep is apt to find that his nervous system and temperament in general is not able to handle the condition of the film.

We try very often to condition people constructively in psychoanalysis, but when we are confronted by persons who spend six to eight hours of the day being adversely conditioned by entertainment, we have very little chance of catching up with the evil that is done by uncontrolled, unregulated entertainment. We carry into sleep the fantasies of the screen or the tube and as a result we have a bad case of insomnia.

Usually we sleep because we are tired. The neurotic is tired all the time, but only mentally and emotionally. The neurotic does not have adequate physical exhaustion or fatigue. Physical activity, well-disciplined but adequate, is extremely useful in producing the pattern of sleep which is proper to the individual. Consequently, the life in which there is a reasonable amount of physical activity is more or less necessary.

Another problem that is being confronted is the ever increasing problem of finance, how to meet and cope with the inflationary cycles that are disturbing us at the present time. Many persons are now being forced to restrict their activities. They are not able to spend the money they would spend normally. If a few seem to have more, there are many who have less, and this problem interferes with man's escape mechanism. If he can go out and spend substantially, if he can travel widely, or if he can entertain elaborately, he has a certain sense of fulfillment.

But if a person who is dependent entirely on what he has for his happiness finds that he is no longer able to indulge these activities, he may develop self-pity. The person who likes to extrovert but because of financial restrictions must sit home or limit his activities as a spender also may be more apt to have emotional outbursts. He is not able to be what he thinks he should be. He is not getting the diversions that he thinks are proper to him.

It all comes back to the essential principle of why we are here. What are we trying to do? Why do we live in this world? Are we here to cover our faults or to get over them? Are we here to nurse our weaknesses or try to correct them? Are we here to be big time spenders or are we here to be big time learners? What is the purpose of life?

Nearly all hysteria arises from false evaluation of purpose. The individual who has no vision of purpose and lives entirely on the pressures of the moment, of course is in a very weak situation. If these pressures become excessive he is in serious trouble. But our real problem here is not to nurse our weaknesses, nor to be always remembering the disasters of the past. It is not even a problem of trying to understand the present administration which is causing considerable activity.

A great many people before this administration gets too much further, one way or another, will have departed from this world anyway, leaving the administration behind. In the course of time we will leave every administration behind. History is proof that we are leaving the past behind every moment. Therefore, while it is proper for us to study processes, look for weaknesses and contemplate correction, these attitudes must be those of a scholar, a student, a young person in school. We are in this world to learn, and it is the learning that counts. When the learning goes sour in ourselves, then we are ready for hysteria. The individual cannot face the lessons and feels that it is his duty to suffer, when it is not his duty to suffer unless he wishes to reject the multiplication table and the alphabet.

We are here to solve the problem of our own existence and in the solving of it to solve the problem of universal existence. They are all tied together. We are in this particular environment because we need it, because we have earned it, and because we have to live out in it many processes and patterns which we established long ago.

If we were born into this world as a neurotic, and a lot of people are, or if we have congenital hysteria, it means we have brought with us a load of unfinished business. It means that we were a failure before or at least we were not completely successful, and if we do exactly what we did before we will stay in hysteria throughout the present life. If, however, we are tired of what we came with and decide that it is better to do something about it, we are not only getting ourselves out of the present emergency but we are curing the larger pattern which we brought with us.

There is nothing we can do in this world that is as valuable as the proper use of the equipment with which we have been endowed. We all have a whole group of values. We have a mind which is either capable of being worn out, tired, miserable, sick and disillusioned, or has a great idealistic opportunity for beauty, wisdom, knowledge, and the searching out of values.

We have emotions which can make us hysterical, can make us hate everything we do and everyone we know, and we also have emotions that have created great music, great art, great literature, and a world of splendid creativity. We do not come into a beautiful, perfect body; we come into a body that we have to take hold of. If we leave it as a fragment of a great descent of biology we have to live with that, but if we find this body needs a little work and we get to work and do it, we gradually transform this body into a magnificent instrument of enlightened purpose. It becomes the link with our world, with humanity, with our neighbor and ourselves.

Through the body we see our own inner life reflected out into the environment in which we live.

Hysteria and hysterical outbreaks all result from mistakes in handling situations. They result from regrets over situations rather than plans for the correction of them. Gradually the individual, wearing down from the pressures of the years, gets tired. When he gets tired he either weakens or relaxes. If in tiring or being tired he loses his faith in humanity, he is in trouble. But if he is tired and relaxes and finds that in the peaceful quietude of relaxation that he can experience for the first time his relationship with the great principles of life, then he is a wiser person.

It is the privilege of everyone to be made wise by age, to learn more — perhaps not all but enough to be better when we leave than when we came.

Hysterical symptoms are simply symptoms of the uncorrected infirmities of our own natures. They result from the misuse of energy. It takes just as much or more energy to worry and to grouch as it does to grow. By using the energy to grow, we improve. Each individual has the opportunity to decide for himself that he is going to use his life allotment, this flow of life from the sun and from the heavens to go through him and come through him into the fulfillment of a more glorious period.